An interesting analysis from Dr David Skilling, Director, Landfall Strategy Group about escalating US fiscal risks:

The UK ‘Truss shock’ provides insight into the growing risks of the unsustainable US fiscal path causing a global financial shock

I was recently quoted in the Financial Times in an article on the global economic and geopolitical spillovers of China’s new manufacturing-heavy growth model:

David Skilling, director at advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group, says “the absorptive capacity of the global economy is limited” and warns that “there’s going to be some real geopolitical blowback” from China’s expansion of high-tech manufacturing…

Skilling says China will not be able pursue these policies “indefinitely” and notes that export flows are already shifting towards economies that are more geopolitically “friendly”, including other members of the Brics grouping, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Latin America, and Africa. But developing economies cannot compensate for reduced access to advanced economies.

The FT article is available here ($): https://www.ft.com/content/ae517907-0244-4344-ad0a-1d029c03555b

I also had a recent op-ed in the South China Morning Post, joint with Donald Low, on these issues together with a perspective on how the Chinese authorities should adjust their economic policy settings. The op-ed is available here: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/opinion/article/3256422/chinas-drive-industrial-dominance-likely-hurt-developing-countries-and-itself?

These perspectives build on recent notes, including this one: https://davidskilling.substack.com/p/china-shakes-the-world

Over the last week, two fantastical events caught my eye. The first was the head of the Congressional Budget Office in the US warning of the ‘unprecedented’ exploding US public debt path, with the potential for a sharp market reaction. The second was advance publicity for a book by former UK PM and policy arsonist Liz Truss, blaming the deep state for her rapid (self-inflicted) political demise.

The two events are linked, with many wondering whether the US is running towards a major fiscal risk event. The likelihood of a ‘Truss shock’ in the US is one of the questions I get asked most frequently in client discussions. The short answer, as discussed briefly in these notes before, is that the risks are growing but we are not there yet.

To think about this, it is useful to distinguish between the fiscal numbers and the surrounding institutions. In the UK context, the market reaction to the Truss/Kwarteng mini-budget was not simply due to the impacts of the announced policies on the UK fiscal outlook – bad those these were – but the surrounding institutional chaos.

In the period before the mini-budget in October 2022, the Permanent Secretary to the Treasury was sacked, jibes were made about ‘Treasury orthodoxy’, OBR guidance on the consequences of the tax cuts was ruled out, and statements were made that more of this type of policy was to come.

Investors were spooked at the removal of institutional safeguards on policy decision-making, which opened up significant downside risk. UK gilts and the currency sold off heavily after the budget announcements, followed by the government’s poll numbers as UK borrowing costs spiked up. Even after these policies were reversed and emergency measures implemented, there were lingering costs (a ‘moron risk premium’ as it was famously called).

UK public debt levels were high and rising before PM Truss took office, and markets had remained calm. Indeed, the UK was not alone in having high public debt levels. The market reaction was in response to UK-specific institutional and political dysfunction. It was concern about institutions, not just the fiscal numbers, that was the catalyst for the shock.

Across the Atlantic

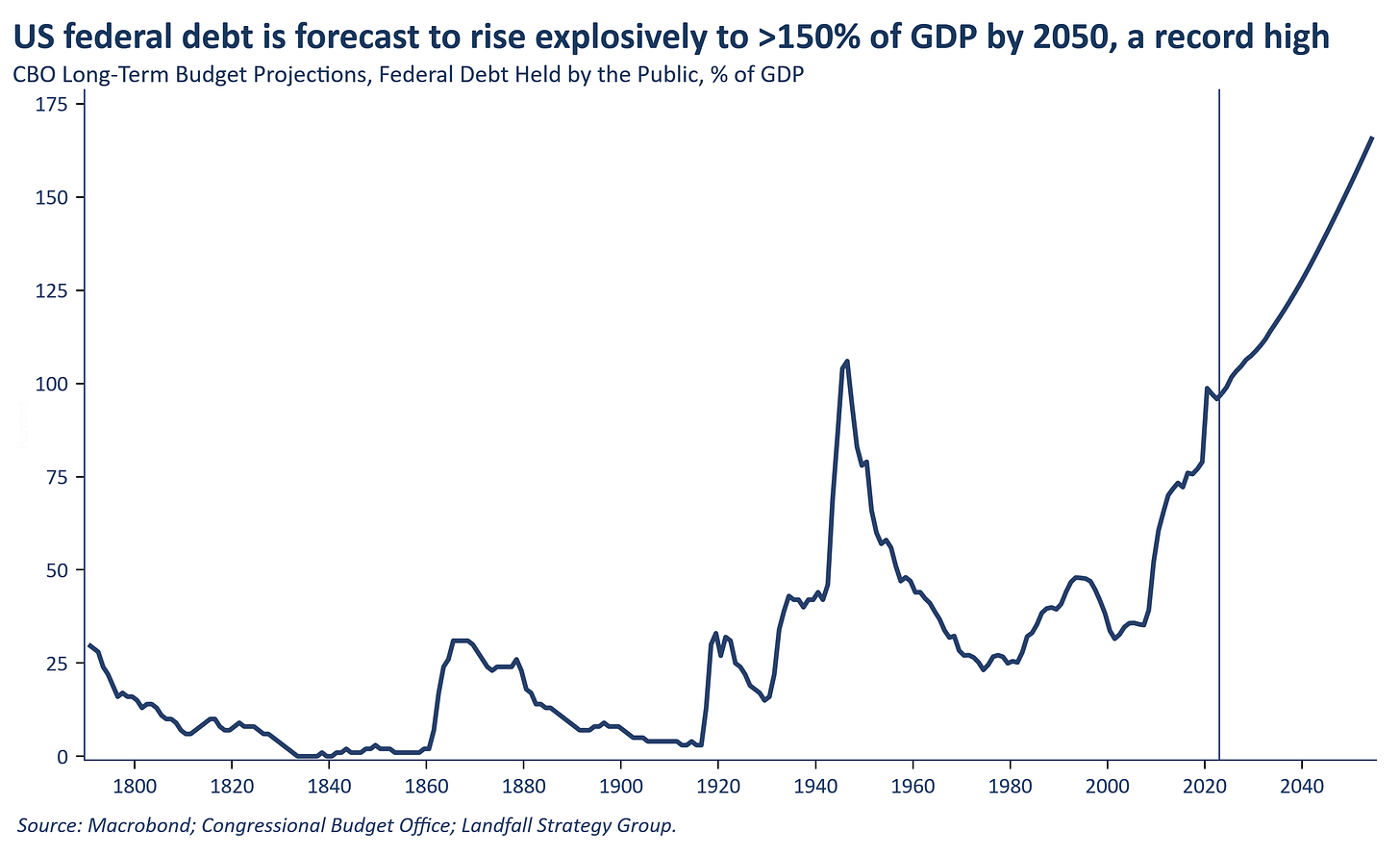

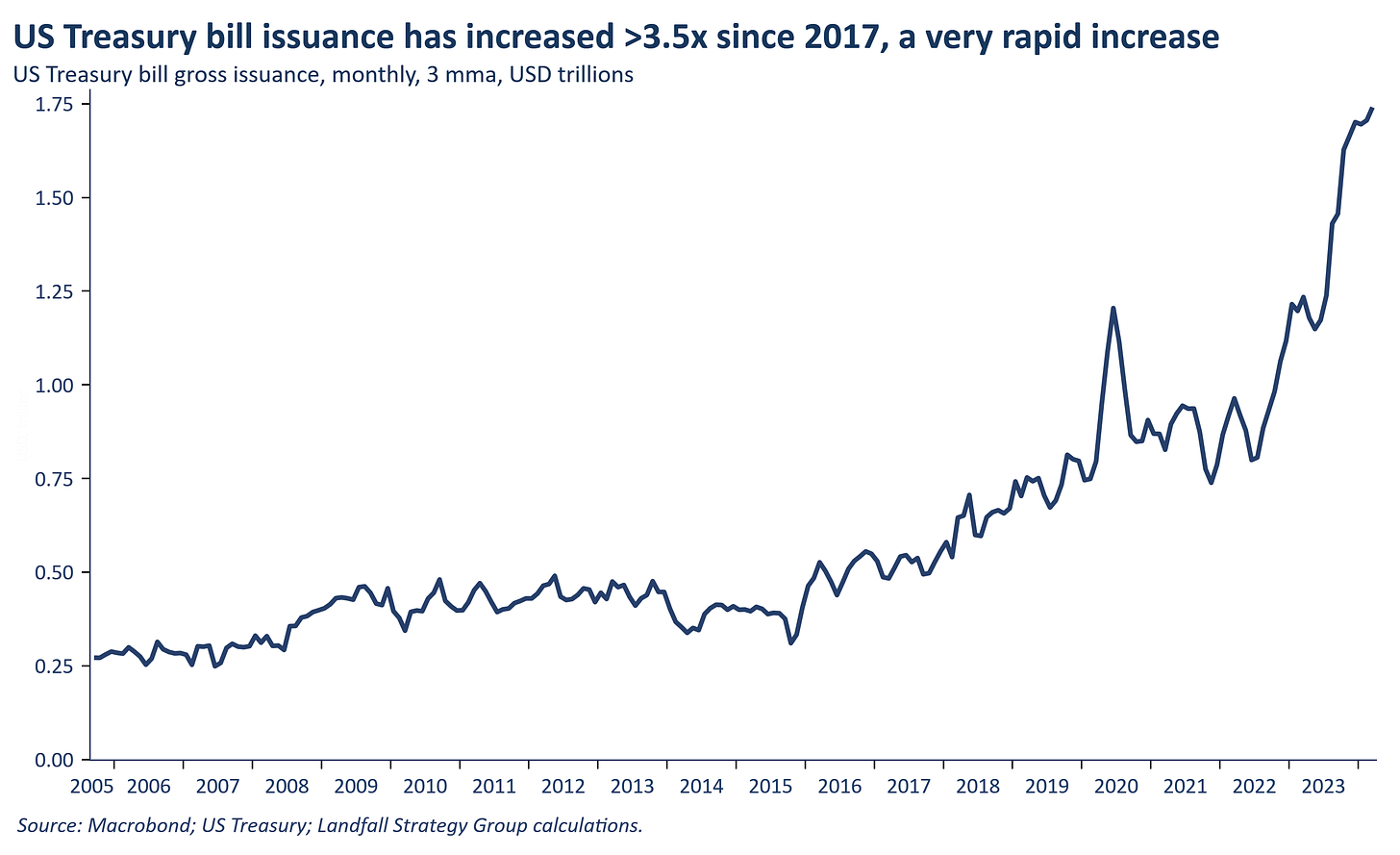

This experience has application to the US. US federal debt is at ~100% of GDP, with a fiscal deficit of 6% of GDP estimated for 2023 (despite strong growth and low unemployment). There is no expectation of a return to fiscal balance anytime soon. The latest CBO forecasts have US public debt increasing to a record high of 116% of GDP over the next decade; and continuing to rise strongly after that.

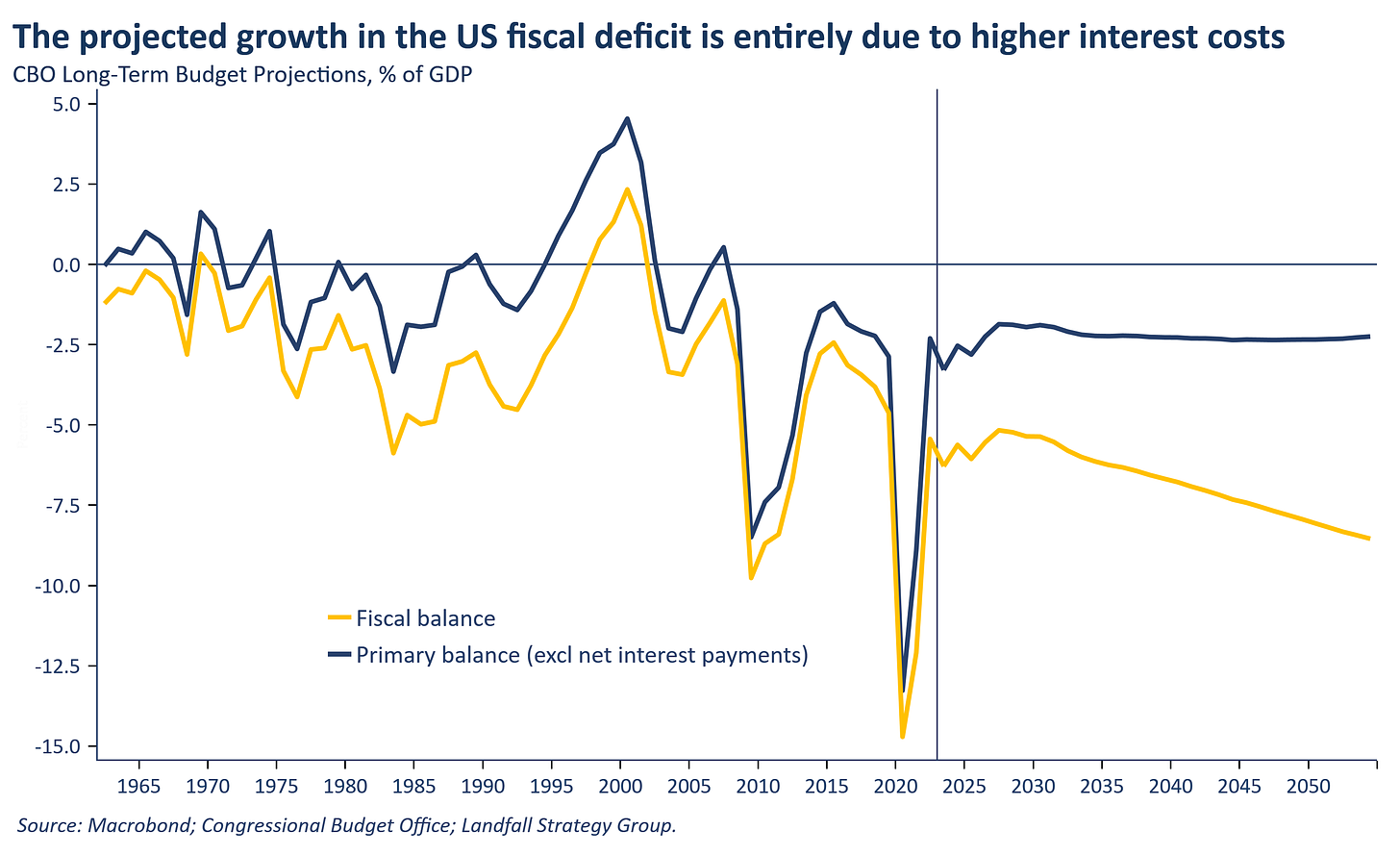

This picture is made more challenging by rapidly rising debt servicing costs: annual interest costs breached USD1 trillion in 2023. Looking forward, the worsening of the fiscal balance is entirely due to higher interest payments: the primary deficit is forecast to remain roughly constant as a share of GDP.

And political dynamics will reinforce the tendency towards fiscal profligacy. The Biden Administration’s recent budget proposal has debt rising further. Mr Trump has not released a detailed fiscal prospectus, but would likely roll over tax cuts passed in his first term (due to expire in 2025) and will not likely cut spending programmes substantially. The changing global economic and geopolitical regime (a ‘wartime economy’) creates spending pressures, which will be difficult to restrain (note the expansive US fiscal policy from the 1960s to the 1980s).

Public debt levels are now at levels not seen since the 1940s. Recent analysis undertaken by Bloomberg shows that the fiscal path is unsustainable to a high level of probability. [As an aside, when I did my PhD on fiscal policy across OECD countries 20+ years ago, I coded economies with public debt >60% of GDP as ‘high debt economies’. This now looks very dated.]

But so far there has been a relatively muted market reaction, despite growing statements of concerns from high profile investors. The term risk premium on US sovereign debt has not risen much, and large debt issuances continue to be received well in the market.

Partly this is because of the depth of the US Treasury market, and the status of the US as the global reserve currency issuer. But if something can’t go on forever it won’t. And meaningful risks are building. So what might be the trigger for a re-pricing? Here, the UK experience is instructive: institutions matter.

Institutional change

The proximate trigger might be a second Trump Presidency. A second Trump Administration would not necessarily be materially less fiscally disciplined than Mr Biden. The bigger issue is that Mr Trump is much less committed to institutions than Mr Biden. No politician likes institutional constraints (which is why they are there), but Mr Trump is more likely to ignore them or blow them up. Mr Biden is (relatively speaking) an institutionalist. The implication is that the fiscal risks increase meaningfully under Mr Trump.

Mr Trump has committed to replace Mr Powell as the Fed Governor (his second term expires in May 2026) on the grounds that he is ‘too political’. Mr Trump is likely to want to appoint someone that will accommodate his policy preferences. If this gets through the Senate confirmation process, this would be a major institutional change.

It would likely accelerate the transition to an era of ‘fiscal dominance’, in which monetary policy is shaped to support fiscal imperatives: keeping interest rates capped and using the central bank balance sheet to buy government debt. There is historical precedent for this in the US (the 1950s) and elsewhere (and most recently in Japan). Given the fiscal starting point, the politics of fiscal consolidation (spending cuts, tax increases) are more challenging than creating fiscal space through accommodating monetary policy.

Moves in this direction would reduce the attractiveness of US debt, causing a major sell off – and leading to a repricing of assets around the world. It would be a major global risk event: the costs of the UK fiscal shock were contained within the UK, this would not be. Market pricing of this possibility would have massive global economic, financial, and geopolitical repercussions, including for fiscally conservative (but globally exposed) small economies.

A second Trump Presidency would have a broad array of global economic and geopolitical spillovers, from the imposition of tariffs to a changed approach to international alliances. But the heightened economic/financial risks from a fiscal shock might be one of the biggest exposures. Mr Trump was good for markets in his first term; but public debt and interest rates are much higher now, and the Trump policy playbook would likely have very different market consequences.

If Mr Biden does win in November (still my base case), the likelihood of a US fiscal shock will also continue to build – but at a slightly slower pace. Over time though, the fiscal math will create political pressure for changes to institutions.

Although the increasingly unsustainable US fiscal path hasn’t yet led to a re-pricing of US debt, firms and investors should not get complacent; things are calm until they’re not. The growing risk of the institutional props for macro policy being kicked away should be taken seriously. That is the sobering lesson of PM Truss for the US.

See the original article here: https://davidskilling.substack.com/p/escalating-us-fiscal-risks